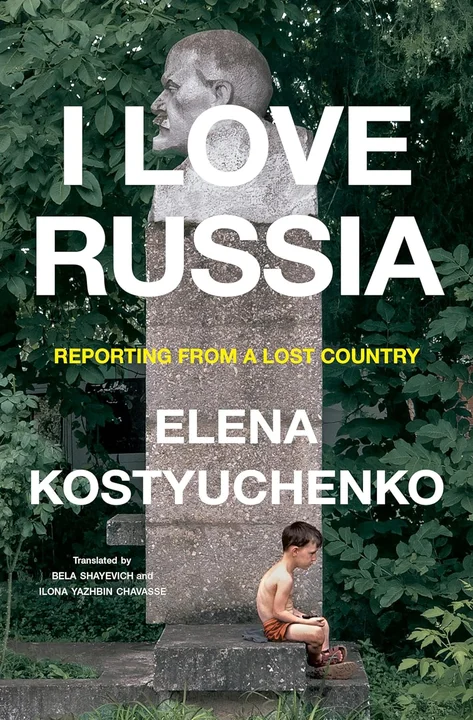

The recent death of Alexei Navalny offered yet another sobering reminder of Vladimir Putin’s relentless crackdown on opposition voices in Russia. Navalny, one of the most prominent critics of Putin’s regime, died in prison on February 16 after years of ill treatment and multiple assassination attempts. Putin has targeted his critics with imprisonment and violence since he came to power in 2000, and journalists have been some of his primary victims.

In "I Love Russia: Reporting from a Lost Country," journalist and outspoken Kremlin critic Elena Kostyuchenko highlights the chilling danger journalists in Russia have faced for decades. Kostychenko interweaves personal essays with articles published during her fifteen plus years writing for Novaya Gazyeta, a preeminent independent Russian newspaper that was shut down in 2022 and now operates in exile from Latvia. These essays paint a grim picture of life in Russia during Putin’s twenty-four years in power, exploring the Kremlin’s brutal repression of free journalism, as well as decades-long economic struggle, widespread homophobia and anti-gay violence, the immense suffering caused by Russia’s invasions of both Chechnya and Ukraine, and more.

Much has been written about contemporary Russia, but "I Love Russia" manages to stand out in this saturated field of scholarship. Through her reporting, coupled with these personal and intimate reflections on her life and career, Kostyuchenko explores individual human experiences of life under Putin’s dictatorship, in addition to the wider societal complexities of post-Soviet Russia. She highlights issues that often don’t make it into headlines and mainstream analysis, including several essays about the indigenous populations of Siberia and the unique challenges they have faced throughout history and in the present. The book also looks at the extreme divide between Russia’s urban centers and its vast rural regions. Though life in Moscow and St. Petersburg has its challenges – particularly for non-Russian immigrants, members of the working class, dissidents, and the LGBT community – the essay “Moscow Isn’t Russia” underscores just how hard and hopeless life can be in Russia’s villages. Exploring these layers of Russian society is especially important right now, given that men from rural, indigenous, and immigrant communities have been disproportionately recruited to fight and killed during Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Despite being a collection of articles and essays, the book manages to tell a cohesive narrative. Kostyuchenko opens with an essay about growing up and discovering her passion for journalism. The essay, “The Men From TV,” appropriately opens the book outlining the primacy of state-owned TV, which generates ubiquitous propaganda. The book’s final essay discusses the shutdown of Novaya Gazyeta just weeks after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the final act of aggression toward the newspaper and its fearless journalists, of whom six have been killed or died under suspicious circumstances. Perhaps the most noteworthy theme throughout the book is Kostyuchenko’s own bravery to continue chasing the truth despite repeated threats and attacks on her and her colleagues. Kostyuchenko humbly acknowledges that, despite their efforts, these journalists were unable to protect their country from descending into pure fascism, unable to save themselves or their compatriots. The book is not an uplifting read but it is an incredibly important reminder of the undying need to protect journalists and freedom of speech.

Skip to main content

Skip to main content